I grew up during the time of

seasons. I suspect that children today don't have a clue about the major

and minor seasons that were an integral part of my childhood.

The major seasons were football and baseball - we didn't consider

basketball a major season, though we did spend some time every week playing

Horse, unless we were caught up in a minor season.

The minor seasons were marbles, yo yo's, rubber guns, and soap box

cars. For clarification purposes, you need to know that a

rubber gun was a homemade weapon that fired rubber strips cut from an

automobile inner tube, and our version of soap box racing had little

resemblance to today's soap box racers that compete at Akron, Ohio. All

we needed to build a soap box racer was three pieces of wood and four wheels

and axles, and a rope for steering.

When Little League Baseball came to my home town, we were excited

for a couple of reasons. The first reason was new baseballs. Most of

us had never seen one, much less played with them. The second, and almost

as exciting as new baseballs, was uniforms. The logistics of bringing

Little League Baseball to our town weren't an issue for us until the day teams

were chosen.

We had exactly enough players for the objective twelve teams.

And wonder of wonders, we had twelve sponsors and twelve big boxes of

uniforms. Then we came up a bit short. We had only eleven coaches

and eleven assistant coaches. The leaders of the organization walked around

the pitchers mound and spoke in low voices for a while. Finally a spokesperson approached us and said, "We have a small problem, but we aren't

going to let that stop us. We going to go ahead and choose teams.

Hit the field boys."

The choosing up process lasted about an hour. Eleven coaches

and their assistants took turns picking players. When it was done each of

the eleven coaches had twelve players and there were twelve of us left on the

field, the ones who weren't chosen in the first twelve rounds. I looked

at my fellow team mates and realized that we were far from the best, with the

exception of Mike Braswell, who was one of the best pitchers in town, but who

was saddled with a father who could rival any of today's Little League manic

parents, which explained his presence with the unchosen.

Before we left the field that first day, we were issued uniforms

by the old man who was heading up the organization of the town's first Little

League Baseball season. He told us when to be back for our first

practice, then he added, "Now don't worry about a thing. You'll have

a coach when you come to back to your first practice."

A few of us met Sunday afternoon and talked about our team

prospects and speculated on who our coach and assistant coach would be.

We didn't have a clue, but we were sure that it wasn't a good sign.

Monday, after school, I walked to the designated practice field.

The man who had assured us we would have a coach was the only adult

present. He called us all to the center of the field. When he had

our attention he smiled and said, "Your coach is on the way and," he

paused, looked at his watch, raised his head, smiled again, and continued,

"and there he is."

My friend, Georgie Gilbert turned around and then exclaimed, "It's

your Daddy!"

I pivoted toward the parking lot just in time to see Daddy jump

out of our car, yanking his tie off as he slammed the door. He waved and

jogged toward us, pulling on his old baseball cap as he came. I saw his

old Carl Furillo glove under his right arm and I knew everything was going to

be Okay. And it was.

Now, I don't mean to imply that we won a lot of games. As a

matter of fact, we only won one regular season game, and that was by forfeit,

when the other team showed up without enough players. As a group, we

weren't great, but the reason was lost games was Daddy's decision to let

everyone play in every game.

That didn't make Daddy popular with all the parents, especially

Mike Braswell's father. In fact, Mr. Braswell became so vocal on one

occasion when Daddy replaced his son with another player, that the umpire

called timeout while Daddy left the bench, went into the stands, and talked to

Mr. Braswell, who turned a number of shocking shades of red and then took Mike

and left the field.

Regardless, we all loved to play in each game and nothing changed

that practice until the regular season ended and the playoffs began.

At a coaches' meeting it was decided that every team would play in

the playoffs, regardless of their record. Before our first playoff game' Daddy gathered us all together in right field, near the fence where he

wouldn't be overheard by the other parents or coaches. He said,

"Boys, we've had a lot of fun this season, haven't we?"

We shouted yes, and he smiled and then continued. "You

all know that we are a better team than our record indicates. I figured

it was more important for everyone to play than to win every game."

Someone shouted, "So we didn't win any games."

Daddy laughed and then said, "That's right, we didn't.

But that can change right now, if you want to win. If you decide

that you do, not all of you will play every game. So, you decide what you

want to do..."

Without meaning to, I shouted,

"Win." Immediately all my teammates joined in the

chant, "Win, win, win!"

I was a pitcher and back-up center fielder. I didn't play in

the first game of the playoffs. Mike pitched every inning, and we won 9 to

2. We were all elated, and Daddy took us to the Dairy Queen for

celebration ice cream.

Since Mike pitched the entire game, the rules said he couldn't

start the next game. I started that game and kept us in it for two

innings. Mike started the third inning and went all the way from there.

We won that one by seven runs.

With Mike pitching, we won the third game, and I realized that our

fan base had grown by about two hundred percent. Since that time, I've

noticed that phenomena applies to most things in life.

We won the fourth game, but it was closer than any of the first

three. With only two undefeated teams left in the playoffs, we found

ourselves on the threshold of playing for the first ever league championship.

Before the championship game, Daddy gathered us in right field

again. "Boys," he said, "The last four games have been fun

but not as much fun as all the games we played before the playoffs

started." He paused, looked at each of us, and then continued.

"Two of you haven't played a single inning, and two more of you have

only played two innings each." He paused a final time, letting his

words sink in, then said, "We can win today and we'll be champions.

Or we can all play and have some fun. I'd like for everyone to

play. What would you like?"

Georgie, who hadn't played a single inning, stood silently staring

at the ground. In fact, it was a long time before anyone said a word.

Finally Mike Braswell said, "Coach, let us all play."

Daddy smiled at him as he said, "Good idea, Mike. Let's

do that."

We all played, and we were beaten by three runs, on the score board, but we won in our hearts where it matters.

Daddy was promoted a couple of months later and his new job took

all of his extra time, so we had a new coach, and even an assistant coach, the

following year. None of that mattered to us. We'd had our

championship season.

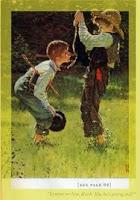

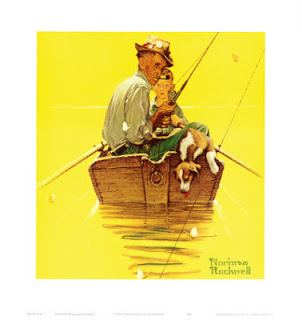

Choosing Up was Number six in my Norman Rockwell blog series.

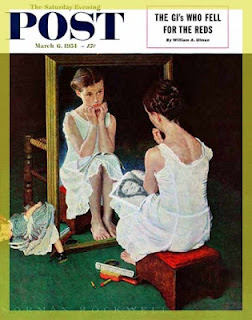

Tomorrow's blog is called Age of Romance. Here's the Rockwell

painting I'll use to illustrate the post.